|

Last Monday, Governor Inslee issued a stay at home order for all people in the state of Washington. In this new reality—a new “normal” of staying put, of not coming and going—our doings are now centered on only what is essential; providing and procuring services that are essential to survival. I was relieved to see that mental health services “officially” qualified. Your therapy is essential. It’s nice to have it said in writing, though it says nothing my own experience hasn’t already told me in ten thousand other and more profound ways. So I’ve been thinking a lot about what’s essential lately. Like food. Eating. It’s at the heart of the great matters of living and dying, as the Buddhist teachings call it (Samsara). When popping over to the store becomes an issue of public health, of possibly endangering other people’s lives as well as your own, but nevertheless remains utterly necessary, suddenly the whole web of interdependence and interconnection that makes this possible becomes palpable in a new way. It gets real, very fast. And I found myself aware that the cashier at the grocery store was risking their life for mine and everyone else who needed groceries. But there’s no way around it. There’s no way to live without harming the other—or being harmed by the other. There’s no way to live without burdening the other—and being burdened. And by ‘the other’ I’m also thinking about nonhumans and the earth. What do you do with that? I found myself going back to one of my favorite pieces of writing by Gary Snyder (which is saying a lot, since I’m a huge fan). It’s actually the last section of his essay, “Survival and Sacrament” in Practice of the Wild. The existential problem (or impossibility) of nonharming is reframed as the problem of Grace—the sacramental nature of all of life. And I love the answer he gives: gratitude. This is the crux of it: “Everyone who ever lived took the lives of other animals, pulled plants, plucked fruit, and ate. Primary people have had their own ways of trying to understand the precept of nonharming. They knew that taking life required gratitude and care. There is no death that is not somebody’s food, no life that is not somebody’s death. Some would take this as sign that the universe is fundamentally flawed. This leads to a disgust with self, with humanity, and with nature. Otherworldly philosophies end up doing more damage to the planet (and human psyches) than the pain and suffering that is in the existential conditions they seek to transcend” (p. 196). Instead of disgust and guilt, gratitude. Welcome to your part in the shimmering web of life. Grace We venerate the Three Treasures [teachers, the wild, and friends] And are thankful for this meal The work of many people And the sharing of other forms of life (p. 198). The altar at Gary Snyder's zendo, Ring of Bone. Photo by Nathan Wirth (thanks!)

Yesterday I went for a walk in my neighborhood. Not my usual walk. I wanted to check out a fig tree that looked from a distance to be full with fruit. My neighborhood used to be, back in the early twentieth century, filled with fruit tree orchards, and some fruit trees still survive “in the wild”—poking out on the edges of cultivated private property, parks, trails, and along major streets. So with this task in mind, I found myself exploring the back country of one of the public garden parks, and then along, but just off, the Chief Sealth trail. Usually I stick to the main street sidewalk and the trail. With a different goal in mind, I started wandering. Though I didn’t find what I was looking for (the tree turned out not to be a fig), I was surprised by what I learned about where I live. And I’ve been here for ten years! There is the stream-carved gully that is paved over at one point by a major thoroughfare. I found several spots where various species of wildflowers and forgotten cultivars are blooming (wild pea vine flowers, which are everywhere right now, an ancient hydrangea and rose bush, different varieties of ferns, delphinia, and others…), and a small DIY farm in a neighbor’s side yard with chickens. Off the Sealth trail, I found a row of blackberry bushes bursting with bounty, some of which I sampled. They’re in a good place where I know they don’t spray and they aren’t exposed to car exhaust. I also came across some interesting poop. Not canine, hopefully not human. Who or what’s been there? Returning home I noticed that my perspective on where I live had changed. It almost seemed like a different place than the one I’ve known for so long. My mind and heart felt oddly more expansive with the new perspective gained simply from getting off the main street and trail and trekking along the edges. That edge between the urban wild and the municipally cultivated. And it wasn't just my perspective on where I lived that changed, but the perspective on where I was. And this shift in perspective stayed with me. I spent the rest of the day marveling at things normally mundane and habitual. That is an example of how Ecotherapy works.  Ecotherapy takes advantage of the wisdom gained from our first teacher and guide: Nature. Focusing attention and the senses upon the natural world, as opposed to the one built primarily by humans, can have a powerfully transformative and healing effect on our thinking and feeling, and especially on the sense of relationship with others, ourselves, and the world around us. Ecotherapy has evolved directly out of the need for deeper connection that the industrialized and high-tech world we live in has created. More plugged in than ever, we are also more disconnected and alienated than ever from others and the direct experience of our world. In the therapeutic relationship, ecotherapy involves enlisting the natural world as a partner. It also involves giving “homework” that helps the client experience first- hand the deepening of their relationship with nature and its profound effects. The therapist helps facilitate and process the meaning of whatever arises for the client in this context. But I’ll tell you a secret. You can also do your own ecotherapy. And, the best part is that it’s FREE! Here’s a practice to try: Take a walk in your neighborhood alone. Leave your cell phone at home, too. Find as many “wild” (not owned or cultivated on any private or municipal property) fruit trees or bushes as you can. Look for wildflowers or forgotten cultivars. Sample or cut if it seems safe/legal and bring your bounty back home. Notice what kind of thoughts and feelings come up for you along the way. It may sound too simple, but as the Ecophilosopher Arne Naess says of such practices: Simple in means, rich in ends.

In honor of the Earth I wanted to post two recordings of talks I attended at Seattle University from two of our most important environmental leaders today in the United States, Bill McKibben and David Loy. In this post I’m going to focus on the more recent talk from McKibben, saving Loy for the next one. If you don’t already know him, Bill McKibben is the author of many books on the environment and the leader of an umbrella organization called 350, which has charged itself with building a broad environmental movement to stop climate change. 350 supports and connects all kinds of environmental actions by partnering with local groups across the world. One of the more well-known actions that 350 has supported, at least among the collegiate crowd, is the student-led movement to push universities and colleges to divest their financial portfolios of funds linked to the fossil fuel industry. As part of this movement, students at Seattle University fought hard to raise support for divestment among students, faculty and staff, and, of course, senior administration. Since the effects of climate change and climate destruction disproportionately affect people living in poverty, and thus communities of color and especially indigenous communities, climate change is not just an ecological issue, it’s an issue of social justice, or more accurately, ecological justice. These are the grounds upon which students at Seattle University are fighting for fossil fuel divestment. Since the university (which is a Jesuit institution) and the Catholic church more generally have long had the mission of creating conditions for social justice in the world, students coalesced under the banner of “reigniting the mission.” Their first proposal to the administration was, however, rejected, but talks with them about divestment are still ongoing. There is hope that soon Seattle University’s financial advisors and Board of Trustees will figure out a way to reinvest the university’s funds in areas that do not promote the destruction of the planet’s habitability for us all, and most significantly in those areas where vulnerable communities of people live and make their livelihoods.

This was the history that had unfolded in the year before Bill McKibben gave his recent Earth Day talk at Seattle University on April 5, 2016. The questions asked centered around climate change, and specifically, the problem of our fossil fuel economy for meeting the goals set by the Paris climate talks back in December of 2015. In Paris, nations across the world, including the United States, met and decided upon the goal of keeping the rise in Earth’s average temperature to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius. McKibben had some sobering news, as usual. February of 2016 was the warmest ever recorded in history—showing an increase in average temperature of 1.5 degrees Celsius—ALREADY. He also talked about the recent investigations into Exxon Mobile and their role in the comprehensive disinformation campaigns about climate change science. Apparently scientists at Exxon knew everything over 30 years ago and mounted a conscious and concerted effort to cover it up (see, for example, http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/exxon-knew-about-climate-change-almost-40-years-ago/) . McKibben’s conclusion: “If you’re investing in Exxon, you’re participating in a charade.” We might well say that this charade is our collective hallucinosis, a kind of “institutionalized delusion,” as David Loy has put it. In my next post, I’ll talk more about what this means in the context of Loy’s talk last May at Seattle University. His is a Buddhist read on this, our shared delusion, the denial of the link between fossil fuel consumption and our climate emergency. Please enjoy listening to McKibben’s talk in full (almost!) here:

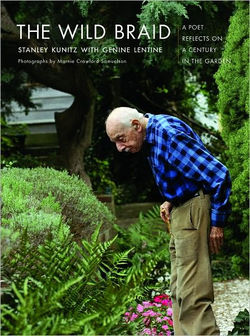

The poet Stanley Kunitz wrote these lines when he was close to the end of his life, which lasted an entire century.

"I am not done with my changes." The layers of lives he lived within, like the successional growth of plants within the garden he tended for decades in Provincetown. While working on the book, Stanley took mysteriously, gravely ill. After three days of living with the proximity of death, he re-emerged, transformed. "The Dark Angel doesn't bring death with him. He brings with him an aura, an intuition. And his contact with you--I'm trying to find the image for it--is an overbearing weight, you're being smothered. At the same time it's like a cloud passing over you that you engage, and it's combined with exhilaration. You meet your destiny, and there is a sense of being given power at the same time." The cloud of unknowing. It was his garden coming to life that he followed back to light. |

AuthorElizabeth Sikes, Ph.D., LMHC Archives

March 2020

Categories

All

|

3136 E Madison st, Suite 300 S, Seattle, Wa 98112

iNTERCONNECTEDCOUNSELING [at] GMAIL [dot] COM

Copyright © 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed